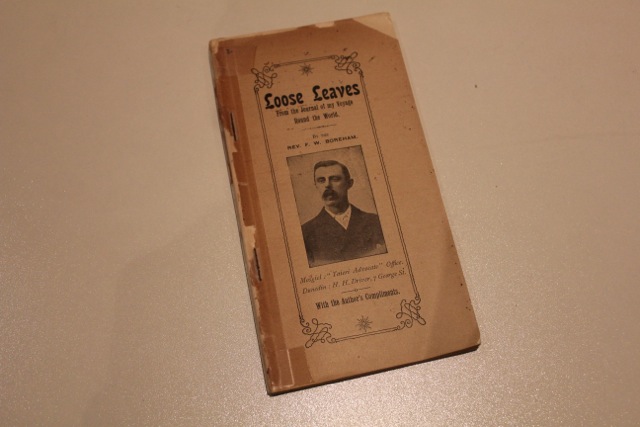

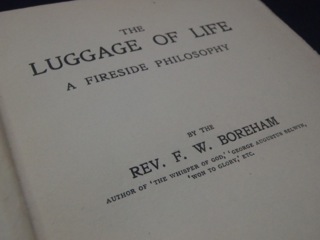

Books By Dr. F.W. Boreham

WHEN SWANS FLY HIGH

PART I

I. THE ORDER MELCHISEDEK…. 11

‘Never again!’ exclaimed Nettie Campbell, with the air of one who, by the skin of her teeth, has escaped with her life. On coming down to hard facts it turned out that, in a weak moment, Nettie had invited the boys in her Sunday-school class to ask questions concerning points that seemed to them obscure. She was astonished at the complexity of the problems that were immediately raised. Like the brave little woman that she is, Nettie grappled valiantly with these profound and ponderous enigmas, and was, as she fancied, approaching firm ground on the other side of the quagmire into which she had inadvertently plunged, when Ted Pringle, who had been relieving the tedium of these abstruse discussions by turning the pages of the epistle to the Hebrews, raised a new spectre with which to paralyse poor Nettie’s powers.

‘What,’ he demanded, ‘is the order of Melchisedek?’

Sparring for time, Nettie suggested that they should look up the passages in which the cryptic phrase occurs. ‘Thou art a priest forever after the order of Melchisedek.’ ‘Another priest should rise after the order of Melchisedek and not be called after the order of Aaron.’ And so on. The expression is used ten times within the compass of a couple of pages, and it was probably this frequent repetition that had caught Ted Pringle’s restless eye.

‘What,’ he blurted out, ‘is the order of Melchisedek?’

Nettie, to show that her discretion was at least equal to her valor, diplomatically replied that she would have to compare the various passages carefully before venturing upon a complete explanation, and, soothing Ted’s troubled mind with a winning and characteristic smile, she promised to deal with the point on the following Sunday. This accounts for her presence at the Manse on the Monday evening.

II

This, of course, is an experience of long ago. But, in the years that have followed, it has often recurred to my mind. I recalled it, for example, in Canada. On the train between Toronto and Montreal, we noticed opposite us a young man and woman, making such strenuous efforts not to look self-conscious that they made us feel how terribly self-conscious they really were. My companion, whose verdicts in such matters I never dispute, explained to me that they were a honeymoon couple; and, seeing that such an elucidation would have never occurred to me, I thanked her for information that made clear much that would otherwise have remained incomprehensible.

From that moment I felt irresistibly drawn to these young people. He was a dapper little fellow, of pleasant countenance and quick nervous movement, nattily dressed, everything about him being brand new. Her apparel was also new; but, somehow, in her case, that factor seemed less pronounced. She was a pretty little thing with very fair hair and pale blue eyes. She tried, almost frantically, to give us the impression that she was completely mistress of herself; and it was no fault of hers that she so pitifully failed. After all, the best of us can only try. In the bustle incidental to the train’s arrival at Montreal, they vanished; and, in their case at least, to be out of sight was to be out of mind. We were ships that had passed in the night, and we never expected to cross each other’s paths again.

In continuing our journey next day, however, we alighted at Quebec to post some letters, and to enjoy a few minutes in the open air, when, whom should we see, similarly employed, but our honeymoon couple of the day before! We fancied that they were a little more at their ease this time, and they even summoned up courage to favor us with a faint smile of recognition. At Sackville, New Brunswick, we left the express and took the local train that conveys those so destined to the ferry that crosses to Prince Edward Island. On this local train we found ourselves again sharing a carriage with the young people. On the boat from Cape Tormentine to Borden we met them several times on deck and in the saloon. On the train from Borden to Charlottetown we were thrown together once more; and, that evening, when we went down to dinner at our hotel at Charlottetown, we found our near friends seated at a table within a few feet of us!

Here the story ends! We never once spoke to them nor they to us. We smiled—they to us and we to them—whenever we met: how could we help it? We got to know their Christian names, for had we not frequently heard them address each other? We felt the deepest interest in them, for, on long journeys, the mind readily concentrates on anything that attracts interest or awakens curiosity. We felt a kind of possessive concern for them. We caught ourselves speaking of them as our honeymoon couple, and, long after we had left the Gulf of St. Lawrence behind us, we would hazard speculation as to how the bride and bridegroom were getting on.

That tour through Eastern Canada was full of fascination and wonder: the views of green hills, blue waters and forest of maple are indelibly imprinted upon our minds. Yet whenever those enchanting scenes rush back upon our memories, we invariably descry our timid little honeymoon couple moving up and down among them. Their romance is our romance. And yet how little we know! And how much there is that we should dearly like to know! How did they meet, and where? How long have they known each other? Is he in a good position, or have they to awaken from their rainbow-tinted dream to face a grim and patient struggle? What led up to this courtship and marriage? And again—where are they now? Has it all turned out as happily as we could wish? Are they both well—and happy—and happy in each other? Has the hand of a little child yet led them into an even deeper and richer felicity? The answers to these questions would be as captivating—at least to us—as the pages of any novel. But these questions can never be answered. The fond pair emerged from the everywhere and vanished into the everywhere again. Like meteors flashing across the evening sky, they shot out of the Vast and into the Vast returned. For us their sweet romance had no beginning and no ending. We cannot trace it back to its source nor pursue it to its climax. It stands there, birthless, deathless. It is a love story after the order of Melchisedek.

III

I remember an afternoon, years ago, in which it fell to my lot to entertain a group of children. It was a birthday, but its joys had been clouded. There were to have been guests, but a variety of reasons had prevented their appearance. Moreover, the day was wet and dreary; and out-of-door frolics were impossible. Suddenly we were startled by a naive suggestion. ‘Take us to the picture!’ cried one of the disappointed youngsters. Straightway they began to tell of the wonderful film that was to be exhibited. Had they not stood open-mouthed before the thrilling and highly-colored portrayals on the hoardings?

The film was entitled The Song of the Circus. Seeing that they had set their hearts upon it, and unwilling to add still further to their disappointments, I feebly took the line of least resistance, and we set out. In the darkened hall, amidst the felicities of chocolates and ice creams, the bleak drizzle and the absent guests were soon forgotten, and, after a comedy or two, The Song of the Circus made its appearance.

The first thing that struck me was that the producer appeared to be taking a good deal for granted. I found it difficult to grasp the relationships in which the various characters stood to one another. Much of the movement completely mystified me, and I could see that my young companions were similarly bewildered.

The second thing that struck me was that our perplexity was evidently not shared by the audience as a whole. Lots of people round about us were applauding excitedly incidents that we were at a loss to understand.

After a while, however, we began to pick up the threads of the story, and were just beginning to feel the thrill of things, when the characters all vanished from the screen, and, in their place, we read a legend to this effect: ‘The Fourth Installment of The Song of the Circuswill appear on Thursday’

It was a serial! We could not return on the Thursday. And so, for us, the story had no beginning and no end. The spice of pathos and humor and tragedy that we had that afternoon tasted was but a part of a larger whole. In our perplexity we attempted to conceive of the instalments that we had not witnessed, and of the instalments yet to come; but it was an utter failure. Our little spoonful of romance had emerged from the Vast and vanished into the Vast again. It was a picture after the order of Melchisedek.

IV

Sitting at the fireside the other evening I picked up a religious journal that my bookseller had just delivered. After glancing over the articles and the news, I found my attention engrossed by the correspondence columns. Two vigorous controversies were in progress. One concerned the matter of Evolution: the other related to the Second Coming of Christ. One of these controversies, that is to say, had to do with the stupendous Programme of the Past; the other had to do with the no less impressive Programme of the Future. As I glanced over the letters that these excellent people had addressed to the editor, I was amazed at the assurance with which many of them tabulated and detailed the things that happened millions of years ago and the things that are to happen in eras yet unborn.

Personally, I have to confess that I simply do not know. I see the remote Past only in shadowy outline; and I see the remote Future through a golden haze. I find a vague hint here and a vague hint there; and, whether looking Backwards or Forwards, I find the study exceedingly captivating. But I swiftly lose myself in infinity. I cannot see at all clearly what happened in the dawn of Time: I cannot see at all distinctly what will happen when Time’s twilight gathers. I see the universe as it now is: I cannot see how it came to be or how at last it will reach its climax and its close. It issues from an obscurity so immense that my little mind staggers in the attempt to comprehend it: it moves towards a destiny so august and so dazzling that I am blinded by excess of light. It is a universe after the order of Melchisedek.

V

In point of fact, I belong to the same order myself. Here I am! There can be no doubt about that. But what of my origin? And what of my destiny? It is as clear as clear can be that my birth was not the beginning of me; and it is no less clear that my death will not be the end of me.

In the course of our stay in Canada, I found myself one afternoon in conversation with an elderly missionary, away in the depths of the great forests. The wine-colored tints of the maples were imparting to the woods their most gorgeous autumn splendor. After watching for a while the antics of the coal-black squirrels gambolling around us, my old friend began to tell of his work, years ago, among the Indians. Nothing had impressed him more, he said, than the fact that the red man always felt, in some vague way, that he had come from Somewhere and was going Somewhere. Out of what immensity had he sprung? Into what infinity was he about to plunge?

‘I remember,’ my companion continued, after directing my attention to the behavior of a chipmunk at the foot of a neighboring hemlock and of a skunk some little distance along the track, ‘I remember being called to an old chief who was dying in his wigwam on the shores of Lake Huron. As I bent over his strangely wrinkled, strangely tattooed and strangely scarred visage, he asked me to repeat to him all that I had said at different times about the human spirit—the real self—the soul that is so much more than the body. He listened with strained attention as I attempted to unfold the mystery.

‘“Yes,” he murmured, “it must be so; it must be so! But where does it come from? Tell me that! Where does it come from? And where does it go to?” He lay perfectly still for a moment, his fine eyes closed and his bronzed countenance looking puzzled but passive. Then suddenly he startled me in a way that I shall never forget. To my astonishment he sat bolt upright, glared at me with eyes that flamed with intensity—almost with anger —and demanded once more, with ten times his former passion, “Where does it come from? And where is it going to?”

‘In the consciousness of his imminent departure, the problem had assumed in the old warrior’s mind, not merely an academic, but a sternly practical, interest. To this day I am often haunted in my sleep by the fire that flashed from his piercing eyes as, in the very act of death, he hurled at me his burning questions.

The red men in their wigwams felt, as we each feel, that we are pilgrims of eternity. Out of the Vast we come: into the Vast we go. By the ordination of a divine will, and by the act of a divine hand, we are made members of the order of Melchisedek.

VI

And He, my Saviour and my Lord, is—so these passages declare—a priest forever after the order of Melchisedek. I see now the meaning of the phrase. It means that I am to take all that I know of Him and project that knowledge into infinity. The order is named after Melchisedek because of the meagreness of our knowledge, and the spaciousness of our ignorance, concerning that royal priest of Salem. He flashes upon our sight in connexion with a single episode. Whence came he? Whither went he? What manner of man was he? What of his parents? What of his children? Who were his predecessors? Who were his successors? Who were his colleagues? It is all hidden from us.

What we know is as nothing when compared with what we do not know. That is the point. What we see of the moth, as it flutters through the shaft of sunlight that streams across the dimly-lighted room, is as nothing in comparison with the entire life-history of the tiny creature. What we saw of the honeymoon couple in Canada was as nothing in comparison with their entire experience and romance. What I know of the universe is as nothing in comparison with the long drama of its age-long progress and development. And, in the same way, what I know of Christ, amazing though it be, is as nothing in comparison with the wealth of revelation that yet awaits my wondering and adoring eyes. All that my Bible, my experience, my teachers, and the testimonies of those who have loved and trusted Him, have unfolded to me of His love and grace and power must be multiplied a million-million-fold; it must be projected back into the eternal Past and forward into the eternal Future.

The revealed is but a drop in the ocean as compared with the unrevealed. We miss the glory of the whole scheme of revelation when we fancy that the sweetest story ever told begins at Bethlehem and ends at Calvary. Like the flight of the tiny moth across the shaft of light, that was merely a sudden and fitful emergence into visibility. He Himself is the kingly head of that most mysterious and most splendid of all ancient orders—the royal and priestly Order of Melchisedek.