home > books by FWB > 1945 A Late Lark Singing > The Swallows on the Telegraph Wire

Chapter X

The Swallows on the Telegraph Wire

As a small boy I was taken by my parents to a tiny fishing village on the Sussex coast, a village that has since developed into a populous and fashionable tourist resort. In the course of that delightful holiday I beheld a spectacle that will haunt my fancy to my dying day. As soon as we had arranged our goods and chattels at the little inn, we strolled down to the front to feast our eyes upon the sea. But it was not the sea that engrossed our attention, The telegraph-wires that ran along the foreshore were black with swallows. The birds were obviously excited. Hundreds of them would fly away and return a little later, as if exercising their wings. The next day the wires were even more crowded and the agitation still more marked. And then, without any sound or signal, off they flew, and, in a dense black cloud, vanished over the watery horizon!

We have all fallen in love with Kingsley’s old gamekeeper at Allfowlsness. ‘He was as good an old Scotsman as ever knit stockings on a winter’s night. He lived alone upon the Ness, in a turf hut thatched with heather and fringed around with great stones slung across the roof by bent ropes, lest the winter gales should blow the hut right away. He minded but two things in all the world, the birds and the Bible!’ When the autumn winds began to blow, and the swallows plumed their wings for flight, the old man, leaning heavily upon his stick, would toddle out upon the moor, doff his cap to them as they departed, wishing them a merry journey and a safe return. Then he gathered up some of the feathers they had left, and went back to read and knit by his winter fire, and to wait patiently for the return of his feathered companions.

I

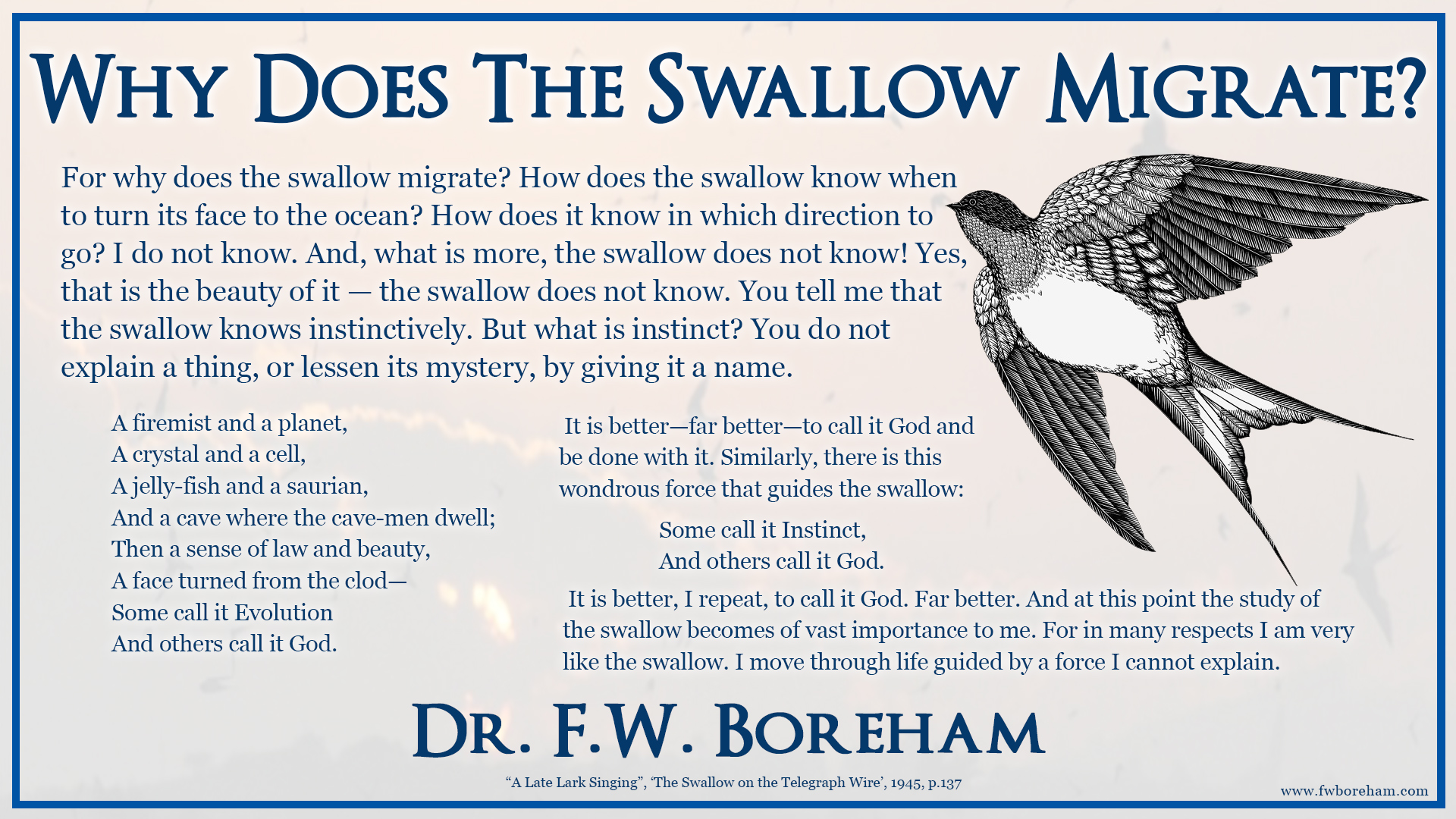

This is all extremely fascinating; and it is so fascinating because it suggests so much more than it actually reveals. For why does the swallow migrate? How does the swallow know when to turn its face to the ocean? How does it know in which direction to go? I do not know. And, what is more, the swallow does not know! Yes, that is the beauty of it — the swallow does not know. You tell me that the swallow knows instinctively. But what is instinct? You do not explain a thing, or lessen its mystery, by giving it a name.

A firemist and a planet,

A crystal and a cell,

A jelly-fish and a saurian,

And a cave where the cave-men dwell;

Then a sense of law and beauty,

A face turned from the clod—

Some call it Evolution

And others call it God.

It is better—far better—to call it God and be done with it. Similarly, there is this wondrous force that guides the swallow:

Some call it Instinct,

And others call it God.

It is better, I repeat, to call it God. Far better. And at this point the study of the swallow becomes of vast importance to me. For in many respects I am very like the swallow. I move through life guided by a force I cannot explain. By what strange impulse was I impelled to follow this profession—this and no other? By what freak of fate did I marry this wife—this and no other? By what stroke of fortune did I settle in this land—this and no other? Looking back on life, it seems almost like a drift; we appear to have reached this position by the veriest chance. The fact is that, like the swallow, we acted instinctively. And that instinct was God! We say with Browning’s Paracelsus:

I see my way as birds their trackless way.

I shall arrive! What time, what circuit first,

I ask not; but unless God send His hail,

Or blinding fireballs, sleet or stifling snow,

In some time, His good time, I shall arrive;

He guides me and the bird. In His good time!

And what of the greatest of all our migratory instincts— the instinct of immortality? For, after all, immortality is an instinct and not an argument. A few may think that they can prove it. But there arc millions who, unable to prove it, nevertheless feel it. Look at the inscriptions on the monuments of antiquity, to be seen at such places as the British Museum. Here are grotesque representations, thousands of years old, of the soul, in the form of a bird, departing from the prostrate body; of the heart being weighed at the judgement of Osiris; and of many similar scenes depicting the fates and fortunes of men and women in the after-life. Why did the Arab bury the horse with his master? Why did the African bury the slaves with their chief? Why did the South Sea Islander bury a bevy of wives with their king? Why did the Maori bury some weapons with the warrior? Nothing can be more intensely impressive than the unanimity with which earnest men in all ages have sensed a life beyond the grave. Whether you turn to the manuscript of the learned sage or to the customs of the most savage barbarian, you are driven to the conclusion that when Almighty God, amidst the glistening dews of creation’s early morning, stooped over Adam’s prostrate clay and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, He at the same time whispered to the conscious instincts of man’s unsullied spirit a radiant promise of immortality.

II

There is, of course, nothing original in all this. Plato argued in the selfsame way more than twenty centuries ago, and Addison, across the ages, answered him:

It must be so! Plato, thou reasonest well;

Else whence this pleasing hope, this fond desire,

This longing after immortality?

’Tis the divinity that stirs within us;

Tis heaven itself that points out an hereafter,

And intimates eternity to man!

The instinct, like the instinct of the swallow, is agelong and universal. It attends us all through life and grows upon us towards the close. We feel that we are greater than the universe; the eternal harmonies are for ever echoing through our souls; however lovely life may be, we feel that there is more, immensely more, to follow. And, when friend after friend departs and human frailties multiply, expectation becomes wonderfully wistful and the dread of death is swallowed up in the hope of life eternal.

In his History of the Girondists, Lamartine has a memorable passage in which he describes Vergniaud and his followers, at the end of their pitiful sufferings, waiting for the hour of execution. Vergniaud cheers his companions by reminding them of the evidence of immortality. And then he concludes by asking: ‘Are not we ourselves the best evidence of it-we who sit here confronting imminent death, yet calm, serene, impassive? What is it that gives us this power but the immortal spirit within?’ On the other side of the Atlantic, Emerson tells of two American senators who each in his own way spent twenty-five years in searching for evidence of the immortality of the soul. And Emerson marvels that they failed to notice that the impulse that prompted them to seek that evidence so patiently through all the years was in itself the strongest proof they could desire. I like to watch the swallow turn its face to the ocean, and set fearlessly out over the waters. If I had no other proof of lands beyond the sea, the instinct of the swallow would satisfy me. ‘Sir,’ says Emerson grandly, ‘I hold that God, who keeps faith with the migratory instincts of the swallows, will keep His word with man!’ It was well and bravely spoken.

It is this migratory instinct in the soul that convinces Hamlet of the futility of suicide:

In the dread of something after death

The undiscovered country from whose bourn

No traveller returns— puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of.

Even children feel the force of it. That is Wordsworth’s idea in We Are Seven. She was a little girl of eight.

‘Sisters and brothers, little maid,

How many may you be?’

‘How many? Seven in all,’ she said,

And wondering looked at me.

‘And where are they? I pray you tell,’

She answered, ‘Seven are we;

And two of us at Conway dwell,

And two are gone to sea.

‘Two of us in the churchyard lie,

My sister and my brother;

And, in the churchyard cottage, I

Dwell near them with my mother.’

It appeared to her questioner that there was matter here for subtraction, but the curly-headed little maiden would not hear of it.

‘How many are you then,’ said I,

‘If they two are in heaven?’

The little maiden did reply,

‘O master! we are seven.’

‘But they are dead; those two are dead!

Their spirits are in heaven!’

’Twas throwing words away; for still

The little maid would have her will,

And said, ‘Nay, we are seven!’

Who has not pitied poor Mark Twain in his frantic search for evidence of a hereafter? He ransacked all the libraries for books, and more books, and still more books. He read everything that had ever been written on the subject. Then, tired out, he laid down the last volume, exclaiming sadly to the woman who was looking after him: ‘No, I don’t believe it! I can’t believe it!’

‘Mr. Clemens,’ the good woman replied, ‘you do believe it! You wouldn’t have read all those books unless you did!’ A subtle and profound philosophy lay there.

III

And what does all this amount to? What practical end does this instinct serve?

It throws a flood of light upon life, ordinary everyday life, and upon our relationships with one another. The memory that stirred the conscience of Augustine St. Clare, and made him feel, in spite of all his behaviour, that slavery was wrong, was the thought of his mother leading him out into the starlit night and saying: ‘See, Auguste, the poorest, meanest slave on our plantation will still be living when all those stars have sputtered out. They will live as long as God lives!’ The stars temporal: the slaves eternal! Then, if both he and his slaves were citizens of eternity, how could he buy and sell them like cattle; how could he torture and terrorize them? And, by the same token, how can I deceive or cheat or debase my fellowman if both he and I are pilgrims through the ages, destined to confront each other again in the land where all earth’s wrongs are righted?

And see what light it throws upon the Cross! The New Testament declares that Jesus brought immortality to light through the Gospel. But there is a sense in which immortality brought Him to light through the Gospel. Is it conceivable that God would have given His well-beloved Son to save-in some attenuated and poverty-stricken sense-men whose lives are bounded by the cradle and the grave? It is because we ourselves are a bunch of everlastings that we need the everlasting light and the everlasting life and the everlasting love that the everlasting Gospel offers.

In the days when every court and castle had its jester, a certain Duke possessed a clown named Wamba to whom he was much attached. To mark his appreciation, he bade him take the Grand Tour. ‘Go abroad,’ he said, ‘see all that there is to be seen; take with you this golden wand; and, if you meet a greater fool than yourself, present him with it!’ On his return, Wamba found the Duke desperately ill. ‘I, too, am going a long journey,’ he told the jester, ‘an even longer journey than yours!’ ‘And is everything ready?’ asked Wamba, ‘are all the preparations made?’ ‘Alas! Wamba,’ answered the Duke, ‘nothing is ready! I have made no preparations!’ ‘Then, surely,’ replied Wamba, ‘it is to you that I must give the golden wand!

The swallow-instinct in our souls tells us of the life that stretches endlessly before us, and Jesus came into the world that, by His redeeming and transfiguring grace, we may make that endless life sublime.

-F.W. Boreham

0 Comments