Chapter VIII

An Epic of Concentration

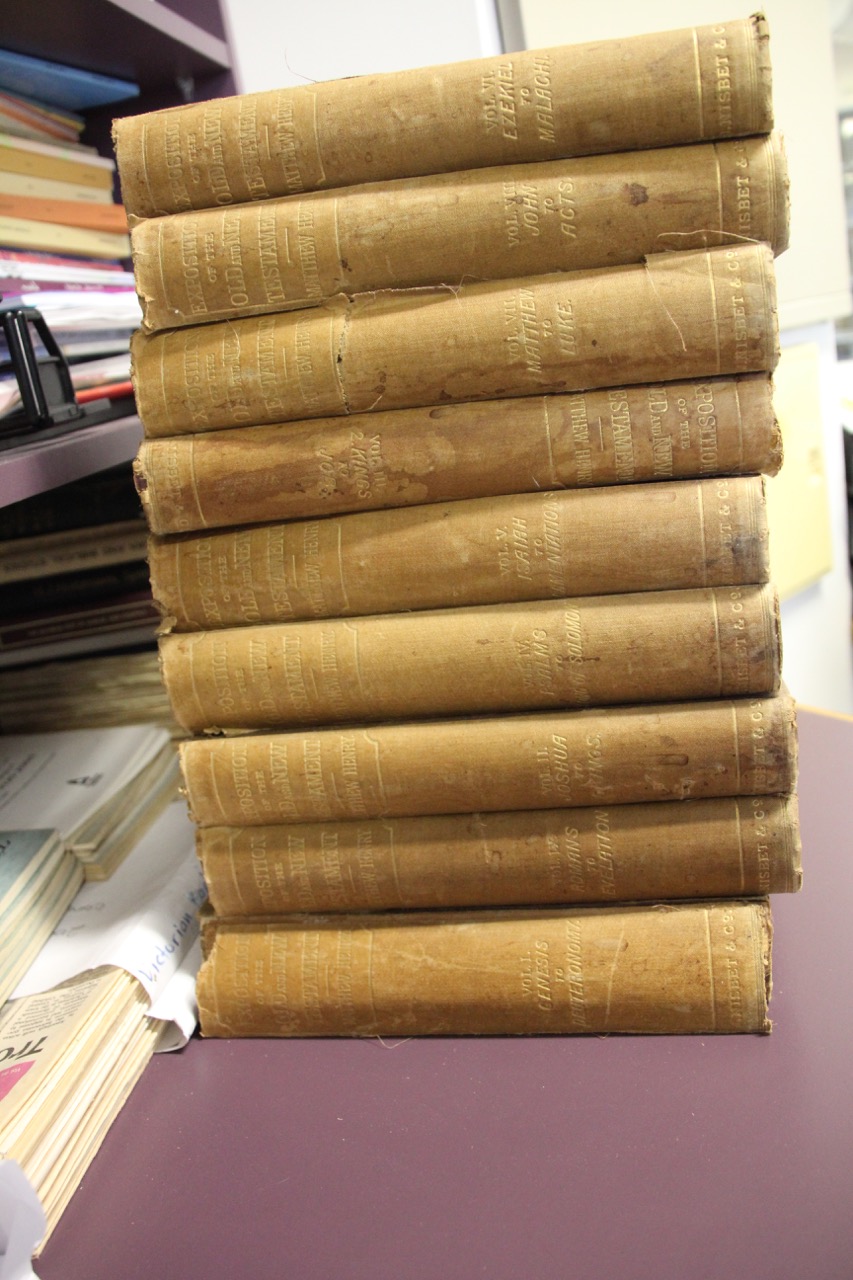

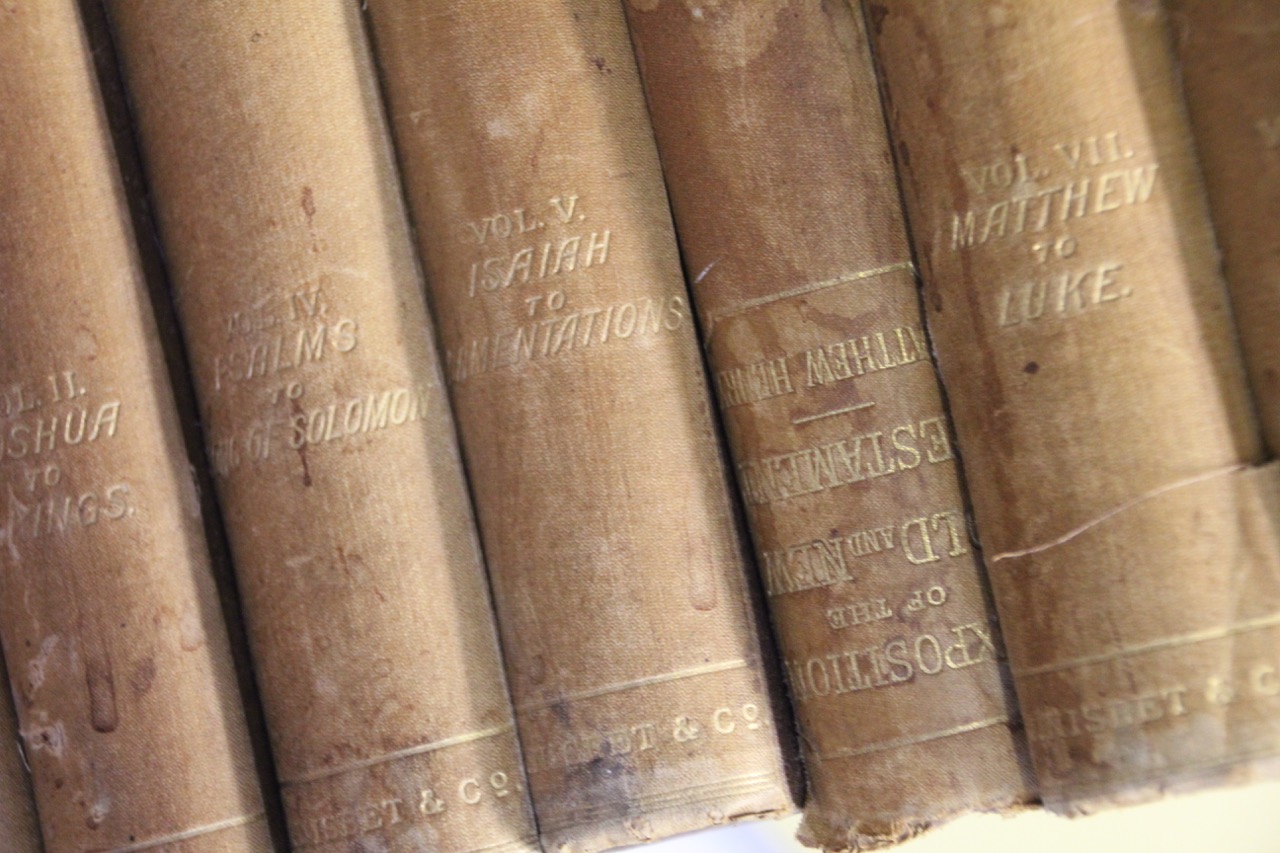

F.W. Boreham’s 9 volume set of Matthew Henry’s commentary on the Bible, on display at Whitley College, Melbourne.

On the bottom shelf of my library there stands, like a foundation stone, a block of nine enormous volumes. As a matter of fact, they are a foundation stone, for they were the first theological tomes that ever came into my possession, and I can never look upon them without a little flutter of emotion.

More than fifty years ago—on Sunday, May 31, 1891, to be precise—the Secretary of the Park Crescent Congregational Church, Clapham, called on me at about ten o’clock in the morning to say that the church was without a minister; that the pulpit supply for that particular morning had failed: would I step into the breach? How I contrived to sustain so vast a responsibility at such meagre notice, I cannot imagine, especially as I find that I took for my text the words: He, through the Eternal Spirit, offered Himself without spot to God. To-day I should need weeks of careful preparation before attempting so abstruse a theme. But perhaps my mind had been occupied with the subject during the days preceding that unexpected summons. At any rate, I struggled through the service, and insuperable obstacles to the immediate appointment of a minister presenting themselves, I was subsequently invited to occupy the pulpit for five months.

Those were the first pulpit steps that I ever climbed, and I often think sympathetically of the long-suffering congregation that survived the daring experiment. When the five months came to an end, it was whispered to me that I was to be entertained at a social evening and made the recipient of a presentation. At that appalling function—appalling to me-I was solemnly presented with the nine huge volumes of Matthew Henry’s Commentary. I remember lugging them home in the rain that night. They have been my companions all through the years. And here they are, faded but intact, to-day.

I

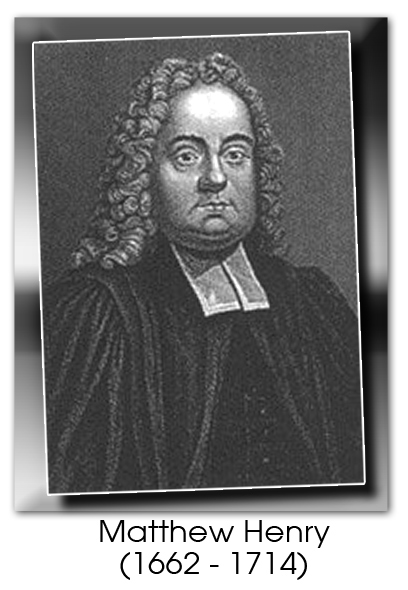

To-day I turn my attention, not so much to Matthew Henry’s Commentary as to Matthew Henry himself. It is an interesting historical excursion. In the days to which it transports us, St. James’s Palace was looked upon as being out in the country, and there were those who wondered if it was quite safe for royalty to reside in a district so secluded.

To-day I turn my attention, not so much to Matthew Henry’s Commentary as to Matthew Henry himself. It is an interesting historical excursion. In the days to which it transports us, St. James’s Palace was looked upon as being out in the country, and there were those who wondered if it was quite safe for royalty to reside in a district so secluded.

The palace grounds were adjoined by a glorious old orchard, the property of one John Henry, a Welshman. John Henry was first gentleman to the Earl of Pembroke. Of the fruit of that dreamy old orchard of John Henry’s I know nothing except that its apples were deemed delicious by the three boys who played there. Those three boys make up an interesting trio. One of them will take his place as King Charles the Second; another will ascend the throne as King James the Second; whilst the third, Philip Henry, the son of the orchardist, is destined to become the father of Matthew Henry, the author of this prodigious commentary of mine, that seems to be bearing the weight of all the books above it.

Philip Henry was very fond of his royal playmates, and sorrowed almost as bitterly as they on that dismal January day on which their father—King Charles the First—was dragged to the scaffold. He was then eighteen. To the end of his days he always felt a little sorry that he had yielded to the temptation to join the great crowd at Whitehall on that bitter afternoon. All through the years he was haunted by the memory of that spacious scaffold, heavily draped in black, relived only by the kneeling-stool—a tiny splash of red velvet. How Philip shuddered, and turned his face for a moment, when, at the stroke of four, the tall figure of the king, garbed only in his sky-blue vest and black velvet breeches, stepped boldly forward, bowed respectfully to the Bishop, and turned his face to the executioner.

Very shortly after that tragic day, Philip Henry resolved to enter the ministry, and, on the completion of his studies, settled at Worthenbury in Wales, where he promptly fell in love with Miss Katherine Matthews, the only daughter of Daniel Matthews, Esq., of Broad Oak, a gentleman of the very considerable wealth and high social status.

Mr. Matthews looked askance at this romantic development. It was by no means a part of his programme that his one and only girl should marry an impecunious young minister.

‘My dear child,’ he argued, ‘this Mr. Henry of yours may be a perfect gentleman, a brilliant scholar, and an excellent preacher; but we know nothing of him! Why, we don’t even know where he came from!’

‘Perhaps not,’ replied the ready-witted daughter, ‘but I know where he’s going, and I want to go with him!’ And, throwing her arms round her father’s neck, she soon wheedled him into giving his consent. They were happily married in 1660, the year in which John Bunyan was thrown into Bedford Gaol, and, two years later, on October 18, 1662, whilst blind John Milton was dictating to his impatient daughters the final stanzas of Paradise Lost, Matthew Henry was born.

I have devoted some attention to Philip Henry because it was Philip who made a commentator of Matthew. Every day of his busy life, Philip gathered his children about him and read the Bible to them systematically, illumining the passage with striking illustrations and homely comments, Matthew and his sisters often made notes of these terse and aphoristic observations, and many of them became the foundation on which Matthew’s masterpiece was built up. When Matthew’s mother read the commentary, she often smiled knowingly when she came upon some of her husband’s familiar quips and sallies.

II

Still, although Philip blazed the trail, it is no small achievement on the part of Matthew to have written, two hundred and fifty years ago, an enormous commentary on the whole Bible which, usually produced in nine portentous volumes, is still familiar to ministers of all denominations in every part of the world. Indeed, it is still being published, both in Great Britain and in America, for, although it has long since been superseded from a critical and academic point of view, it is treasured-and is always likely to be – for its penetrating insight, its exhilarating freshness and its ingenuity of thought and expression.

One of the most intriguing illustrations of the far-flung influence of Matthew Henry occurs among the records of Abraham Lincoln. At the age of seventeen, Lincoln, then a gawky young backwoodsman, was invited to his sister’s wedding. To the astonishment of the other guests, he offered to sing a song of his own composition. No record was kept of the tune, which, perhaps, is just as well; but the words are obviously a paraphrase of a well known comment of Matthew Henry’s.

Matthew Henry’s relatives and friends always thought that the best thing that he ever wrote was his observation concerning the creation of Eve. ‘The woman’, says Matthew Henry, ‘was made out of a rib taken from the side of Adam; not made out of his head to rule over him; not out of his feet to be trampled upon by him; but out of his side to be equal with him, under his arm to be protected, and near his heart to be beloved.’

Now the rough-and-ready verses that Abraham Lincoln sang at his sister’s wedding ran like this:

The woman was not taken

From Adam’s feet, we see;

So he must not abuse her

The meaning seems to be.

The woman was not taken

From Adam’s head, we know;

To show she must not rule him —

Tis evidently so.

The woman she was taken

From under Adam’s arm;

So she must be protected

From injuries and harm.

The quaint verses, as anyone with half an eye can see, are merely Matthew Henry turned into rhyme. But what did Abraham Lincoln at seventeen know of Matthew Henry? Yet one remembers an incident described by Judge Herndon—a thing that happened some years before Abraham Lincoln’s birth. A camp-meeting had been in progress for several days. Religious fervour ran at fever heat. Gathered in complete accord, the company awaited with awed intensity the falling of the celestial fire. Suddenly the camp was stirred. Something extraordinary had happened. The kneeling multitude sprang to its feet and broke into shouts which rang through the primeval shades. A young man who had been absorbed in prayer, began leaping, dancing, and shouting. Simultaneously, a young woman sprang forward, her hat falling to the ground, her hair tumbling about her shoulders in graceful braids, her eyes fixed heavenwards, her lips vocal with strange, unearthly song. Her rapture increased until, grasping the hand of the young man, they blended their voices in ecstatic melody. These two, Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks, were married a week later, and became the parents of the great President.

Now, Peter Cartwright and the other camp-meeting preachers would certainly be familiar with Matthew Henry. Perhaps Nancy heard the saying quoted by one of them, and, later, taught it to her son. However that may be, it is interesting to know that, at that formative stage of his epoch-making career, the noblest of the American Presidents was sitting at the feet of our English Puritan.

III

It was in 1687, when England was seething with discontent and insurrection, that Matthew Henry, after having toyed with the idea of becoming a lawyer, followed in his father’s footsteps, and, at the age of twenty-five, entered the ministry. He settled at Chester, and remained there until very nearly the end of his days. The famous commentary grew naturally out of the conditions that obtained in those leisurely days. Matthew Henry’s congregation assembled twice every Sunday—at nine in the morning and three in the afternoon. In the morning he preached for an hour on a chapter of the Old Testament, beginning at the first of Genesis and going on in proper sequence. In the afternoon he preached for an hour on a chapter of the New Testament, making his way through these, too, in their natural order.

At his week-night service, held on Thursday evenings, he delivered a series of lectures on The Questions of the Bible. He began in October, 1692, with the question addressed to Adam: Where art thou? and he concluded the course, which had occupied twenty years, in May, 1712, when he arrived at the question at the end of Revelation: What city is like unto this great city? It is easy to see that a ministry modelled on these lines would lend itself naturally to his concentration upon his magnum opus.

It was in 1704—seventeen years after his settlement at Chester—that he conceived the general project of his masterpiece. He tells the story in the temper in which Gibbon tells us of the moment at which he first formed the idea of writing the Decline and Fall. Here is Matthew Henry’s record:

‘Nov. 12, 1704, This night, after much searching of heart, and after many prayers concerning it, I began my Notes on the Old Testament. It is not likely that I shall live to finish it, or, if I should, that it should be of public service; yet in the strength of God, and I hope with a single eye to His glory, I set about it. I approach the task with fear and trembling, lest I exercise myself in things too high for me.’

He was then forty-two. He lived to complete the Notes on the Old Testament and was well into the New when, on June 22, 1714, death overtook him. He aimed at completing a volume every two years. In its original form the enormous work consisted of six volumes. His one great desire was that his mother-the young lady who knew her own mind concerning her love affairs in 1660—should live to read at least the earlier volumes. His father had died, at the age of sixty-five, nine years after Matthew had settled at Chester and before the commentary was thought of. His mother read the first volume, and probably saw the manuscript of the second. She died in 1707, having endeared herself to all who knew her by a life of singular strength, sweetness, and grace. Seven years later, at the age of fifty-two, her illustrious son’s strength began to fail. On April 17, 1714, he writes: ‘Finished to-day the fifth volume, bringing my work down to the Book of Acts.’

He was then forty-two. He lived to complete the Notes on the Old Testament and was well into the New when, on June 22, 1714, death overtook him. He aimed at completing a volume every two years. In its original form the enormous work consisted of six volumes. His one great desire was that his mother-the young lady who knew her own mind concerning her love affairs in 1660—should live to read at least the earlier volumes. His father had died, at the age of sixty-five, nine years after Matthew had settled at Chester and before the commentary was thought of. His mother read the first volume, and probably saw the manuscript of the second. She died in 1707, having endeared herself to all who knew her by a life of singular strength, sweetness, and grace. Seven years later, at the age of fifty-two, her illustrious son’s strength began to fail. On April 17, 1714, he writes: ‘Finished to-day the fifth volume, bringing my work down to the Book of Acts.’

In 1712, after twenty-five years at Chester, he had accepted a call to Hackney in London. In taking farewell of his Chester congregation, however, he had promised that he would come back to preach to them at least once a year. He kept his pledge in 1713 and again in 1714; but, on his return journey after this second visit, his horse threw him; and, although he denied that he had sustained any injury, he was never the same again. He died a month or so later.

‘You have been used,’ he said to a friend who sat beside his bed, ‘you have been used to take notice of the sayings of dying men: this is mine: that a life spent in the service of God is the most pleasant life that anyone can live in this world!’ With which provocative and characteristic comment we may very well take leave of him.

-F.W. Boreham

https://youtu.be/pS7uUpjUgdY

-

NAVIGATING STRANGE SEAS, The Dr. F.W. Boreham Story, Episode 1 – England (DVD)

$7.95 -

NAVIGATING STRANGE SEAS, The Dr. F.W. Boreham Story, Episode 2 – New Zealand (DVD)

$7.95 -

NAVIGATING STRANGE SEAS, The Dr. F.W. Boreham Story, Episode 4 – Melbourne (DVD)

$7.95 -

NAVIGATING STRANGE SEAS, The Pastoral Pilgrimage of Dr. F. W. Boreham – Blu ray Disc

$9.95