home > books by FWB > 1945 A Late Lark Singing > A Splinter of Stone

Chapter VI

A SPLINTER OF STONE

I came recently upon an old cemetery that has been converted into a public garden-a thing of flower beds and fountains and pleasant walks. The tombstones that once marked the graves now stand around the wall. Most of them are indecipherable: many are broken. Among the latter I found one fragment that bears but three words of the original inscription. Only three words; but such words! More than conqueror!

That splinter of stone reminds me of Oliver Cromwell and of Catherine Booth. It was on Friday, August 20, 1658, that George Fox went down to Hampton Court to see Oliver Cromwell concerning the persecution of the Quakers. Fox was a young fellow of thirty-four; Cromwell was in his sixtieth year. As he entered the park, Fox saw Cromwell riding bravely at the head of his Life Guards. But, well as Cromwell looked, Fox felt a whiff of death go forth against him. I have no idea as to what Fox means, and I doubt if anybody else has; but I suppose that Quakers of the mettle of George Fox experience sensations and repercussions of which ordinary mortals know nothing. However that may be, Oliver Cromwell died within a fortnight of that meeting; but not until, on his sick-bed, he had murmured again and again, ‘I am a conqueror, and more than a conqueror, through Him who loveth me!’

Who that was in London (as I was) on October 14, 1890, can forget the extraordinary scenes that marked the funeral of Catherine Booth? It was a day of universal grief. The whole nation mourned. For Mrs. Booth was one of the most striking personalities and one of the mightiest spiritual forces of the nineteenth century. To the piety of a Saint Teresa she added the passion of a Josephine Butler, the purposefulness of an Elizabeth Fry, and the practical sagacity of a Frances Willard. The greatest in the land revered her, trusted her, consulted her, deferred to her. The letters that passed between Catherine Booth and Queen Victoria are among the most remarkable documents in the literature of correspondence. Mr. Gladstone attached the greatest weight to her judgement and convictions. Bishop Lightfoot, one of the most distinguished scholars of his time, has testified to the powerful influence which she exerted over him. And whilst the loftiest among men honoured her, the lowliest loved her, as those dense black crowds eloquently proved. And what was the text that dominated that unforgettable occasion? It was the text that was inscribed upon the brass plate on the coffin, and, afterwards, on the stone-work round the tomb: More than conqueror! She had known stress and strain, persecution and pain, such as fall to the lot of few women: yet, in spite of it all, she was more than conqueror through Him who loved her.

I

The house is hushed. People move about on tip-toe. A doctor is in attendance. A nurse flits hither and thither. Somebody dying? you naturally inquire. No; somebody being born. Somebody, that is to say, beginning to live; somebody beginning to fight; somebody beginning to die. We need not stress the first point—beginning to live—it is so obvious. Nor the last—beginning to die—it is, we may hope, so remote. But beginning to fight! That is the thing that matters. For this newcomer is a born warrior. He fights for his first breath: he will fight for his last breath: and he will fight all the way from the one to the other.

Beyond the shadow of a doubt, the dominant note in all human experience-and especially in all Christian experience-is the militant note. Life is a fight, and a fight to a finish. Every man is engrossed in a desperate struggle, and his one aspiration-the dream of all his days-is the dream of conquest.

I went on Saturday to see a cricket match. It was a school match — Scotch versus Wesley—on the Scotch College ground. It had rained all night, and I was not at all sure that play would be possible. This may have accounted for the fact that I arrived a few minutes late. When I alighted from the tram I saw two or three very small boys, wearing Scotch College caps, playing near the gate.

‘Is there to be any cricket?’ I asked,

‘Oh, yes,’ replied one of these youngsters, brightening excitedly.

‘They’re playing now, Four wickets down for three runs!’

I felt that I was missing something, and hurried my steps along the gravel path towards the oval. But, before I reached it, I became conscious that I was being pursued. Glancing back, I found myself confronting the boy who had given me the score. He was out of breath; but, so soon as he could recover his powers of speech, he exclaimed:

‘I forgot to tell you: it’s Wesley batting!’

I assured him that I had formed that impression from our earlier interview. But, in his anxious eyes, I caught a glimpse of warrior pride. He could not bear to think that, even for a few moments, I should fancy that it was his team that was being routed.

II

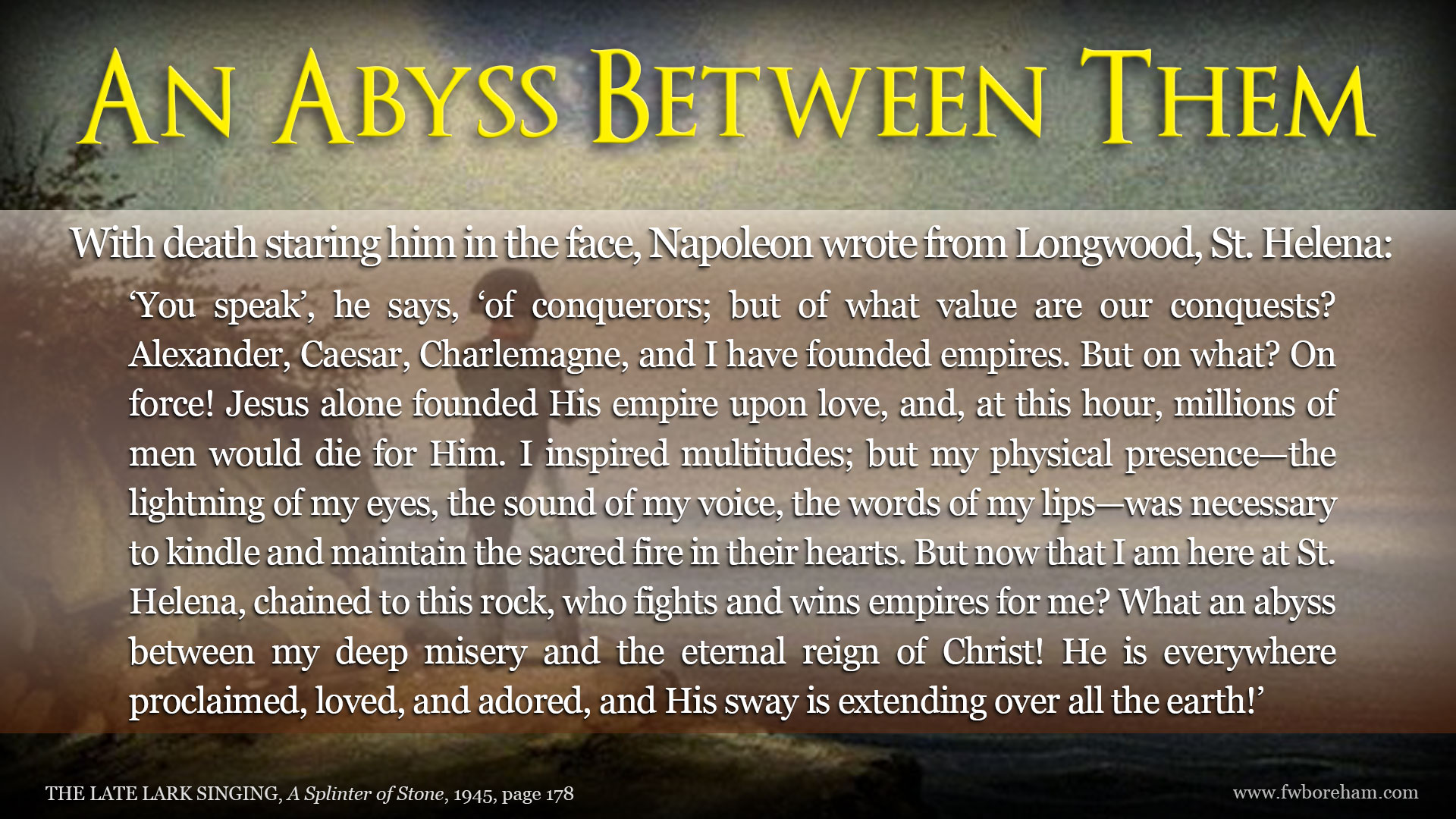

But more than conqueror! What is it to be more than conqueror? The best way of showing the size of a monument is to let a man stand beside it. Through Christ’s great grace, Paul says, we may be more than conquerors. Let the conquerors, the most glorious conquerors of the ages, stand beside Him, and see how He dwarfs them all! Therein lies the significance of that poignant letter that, with death staring him in the face, Napoleon wrote from Longwood, St. Helena:

‘You speak’, he says, ‘of conquerors; but of what value are our conquests? Alexander, Caesar, Charlemagne, and I have founded empires. But on what? On force! Jesus alone founded His empire upon love, and, at this hour, millions of men would die for Him. I inspired multitudes; but my physical presence—the lightning of my eyes, the sound of my voice, the words of my lips-was necessary to kindle and maintain the sacred fire in their hearts. But now that I am here at St. Helena, chained to this rock, who fights and wins empires for me? What an abyss between my deep misery and the eternal reign of Christ! He is everywhere proclaimed, loved, and adored, and His sway is extending over all the earth!’ Alexander, Caesar, Charlemagne, and Napoleon were conquerors: who can doubt it? But stand them beside Christ, as you stand the man beside the monument, and you begin to see the significance of Paul’s immortal phrase. They are conquerors: He is more than conqueror; and we may be more than conquerors through Him.

III

There is no painting in our Melbourne Art Gallery of which I am more fond than of Mr. St. George Hare’s Victory of Faith. It presents two young girls-one of white skin and one of black — awaiting martyrdom in an ante-room of the arena. On the morrow they are to be thrown to the lions. And how are they spending their last night on earth? With their arms lightly thrown about each other’s shoulders, they are fast asleep. And Mr. St. George Hare calls it The Victory of Faith. Victory-over what? Victory over all the might of the Caesars: what do they care for the tyranny of their persecutors? They are sweetly sleeping! Victory over all their feminine frailties: the lions have lost their terror; they are in the land of lovely dreams! Victory over all racial prejudice: black and white are in each other’s arms! Victory over death, for, to them, death has no more terror than the slumber in which they are now indulging.

I have sometimes thought that Mr. St. George Hare must have had this passage of Paul’s open before him as he painted his noble picture. Who shall separate us from the love of Christ? Tribulation? Distress? Persecution? Famine? Nakedness? Peril? Sword? Here is a terrifying array of antagonisms! And every one of them is to be seen in the painting. And to this formidable list, Paul bravely answers, Nay, in all these things-the things in the list; the tilings in the picture-we are more than conquerors through him that loved us.

As I glance once more at the picture of these two girls, whose nakedness is but the emblem of the fact that they have been stripped of everything, I see three possibilities open to them. They might have spent that last night bemoaning their lot and conjuring up horrifying visions of the coming day. That would have been the defeat of faith. They might have huddled together, clasping each other’s hands, grimly resolving to be loyal to their Lord, come what might. That would have been the triumph of faith. But they did neither of these things. They just lay down and slept! And, sleeping, they revealed themselves as more than conquerors through Him whose love and care they never for a moment doubted.

IV

If I were asked to point an inquirer along the road that leads to this superlative conquest, I think I should tell the story of Donald Menzies. He is, of course, one of the rugged characters given us by Ian Maclaren, and, in most of the editions of Beside the Brier Bush, a fine portrait of Donald Menzies, by William Hole, R.S.A., enriches the volume.

Donald sounded all the depths of spiritual dereliction. His depression knew three zones. He was sometimes content to liken himself to Achan, the troubler of Israel, who laid his covetous band upon the accursed thing. More frequently he insisted that, like Simon Peter, he had repeatedly denied his Lord. And, when things with Donald were at their worst, he would link his name with that of Judas Iscariot: with a kiss he had chosen the lot of the betrayer.

At length, however, there came a day on which, out of sheer pity, his minister went to see how it fared with poor Donald. To his astonishment, he met Donald: a new Donald; a Donald with his head in the air and his face shining. The two men walked side by side for awhile among the primroses, with a bank of golden gorse beside them and the stream babbling over the stones at their feet.

Then, at last, Donald spoke. He had been sitting in his cottage, reflecting upon his terrible transgressions, when all at once a word flashed into his mind. The blood of Jesus Christ, His Son, cleanseth us from all sin. It was, Donald said, like a gleam from the mercy seat. It seemed to still everything. He waited awhile to see if anything else could be said to contradict or counteract that one tremendous word. There was none.

‘I leaped to my feet’, Donald explained, his eyes ablaze with triumph, ‘and I looked round, and there was Janet sitting in the opposite chair. Sensing the struggle in her husband’s soul, she was repeating to herself, Thank be unto Cod which giveth us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ.’

That is the first step on the road to conquest. And he who takes that road, and follows it, will find himself, not only a conqueror, but more than a conqueror through the Saviour’s deathless grace.

– F.W. Boreham

0 Comments