home > books by FWB > 1914 Mountains in the Midst > Section 1, Chapter 8, THE PIONEER

VIII

THE PIONEER

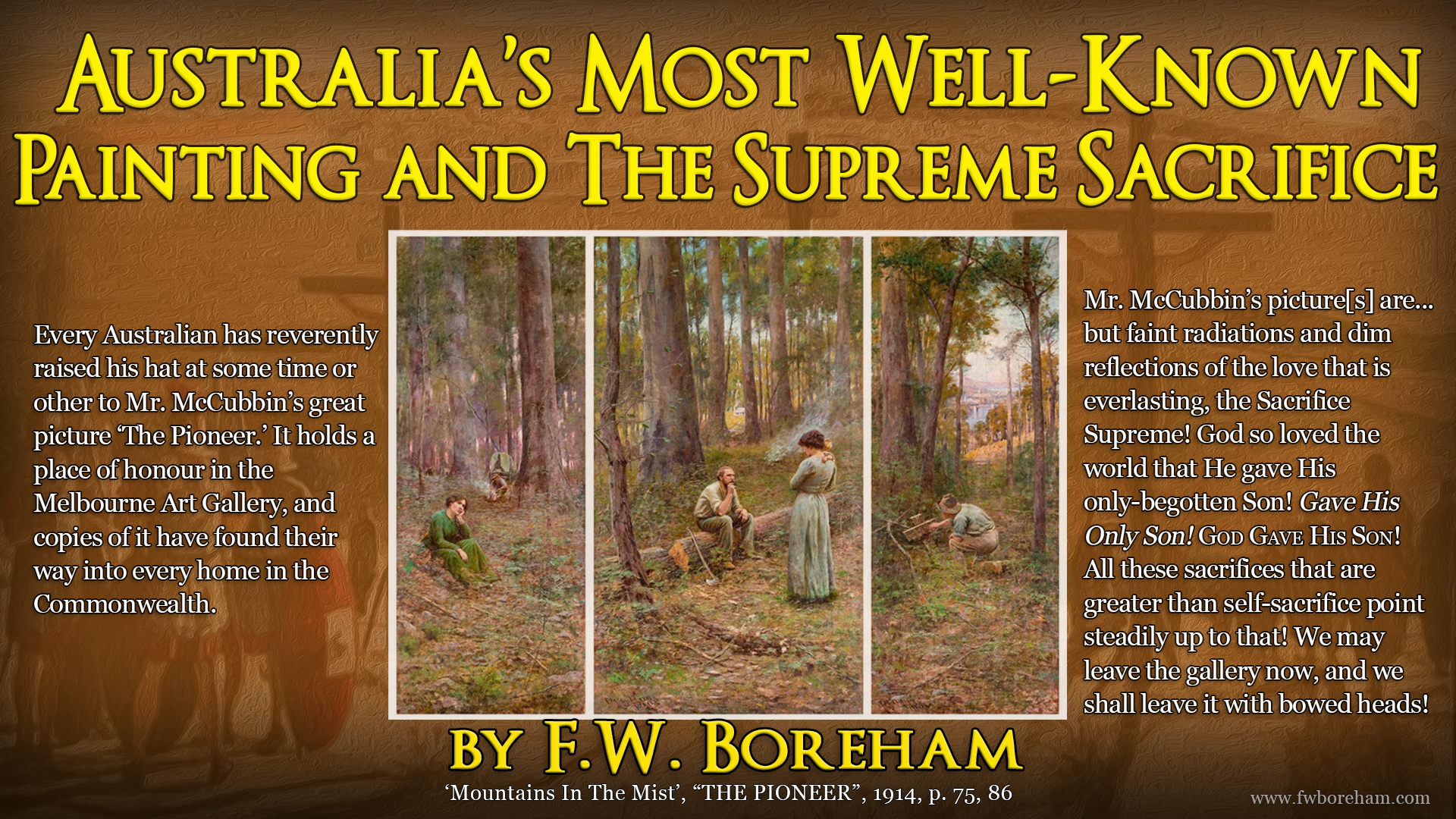

Every Australian has reverently raised his hat at some time or other to Mr. McCubbin’s great picture ‘The Pioneer.’ It holds a place of honour in the Melbourne Art Gallery, and copies of it have found their way into every home in the Commonwealth. I speak of it as a picture; but it is really three pictures in one frame.

The first of the set represents the pioneer on pilgrimage. There stands the wagon! The horses are turned out to forage for food among the scrub The man himself is making a fire under a giant blue-gum. And, in the very foreground, sits the sad young wife, her chin resting heavily upon her hand, and her elbow supported by her knee. Her dark eyes are eloquent with unspeakable wistfulness, and her countenance is clouded with something very like regret. Her face is turned from her husband lest he should read the secret of her sorrow, and see that her heart is breaking. She is overwhelmed by the vastness and loneliness of these great Australian solitudes; and her soul, like a homing bird, has flown back to those sweet English fields and fond familiar faces that seem such an eternity away across the wilds and the waters. The pioneer’s wife!

The centre picture — the largest of the trio-shows us the freshly built home in the depths of the bush. The little house can just be seen through a rift in the forest. In the foreground is the pioneer. He is clearing his selection, and rests for a moment on a tree that he has felled. His axe is beside him, and the chips are all about. Before him stands his wife, with a little child in her arms. The soft baby-arm lies caressingly about her shoulders.

In the third picture we can see, through the trees, a town in the distance. In the immediate fore-ground is the pioneer. He alone figures in all three pictures. He is kneeling this time beside a rude wooden cross. It marks the spot among the trees where he sadly laid her to rest.

The pioneer! It is by such sacrifices that these broad Australian lands of ours have been consecrated. Oh, the brave, brave women of our Australian bush! We have heard, even in Tasmania, of their losing their reason through sheer loneliness; and too often they have sunk into their graves with only a man to act as nurse and doctor and minister and grave-digger all in one. George Essex Evans has sung sadly enough:

The red sun robs their beauty, and, in weariness and pain,

The slow years steal the nameless grace that never comes again;

And there are hours men cannot soothe, and words men cannot say —

The nearest woman’s lace may be a hundred miles away.

The wide bush holds the secrets of their longing and desires,

When the white stars in reverence light their holy altar fires,

And silence, like a touch of God, sinks deep into the breast —

Perchance He hears and understands the women of the West.

Yes; there is a world of pathos and significance in that solitary grave in the lonely bush. And he who can catch that mystical meaning has read one of life’s deepest and profoundest secrets. He is not very far from the kingdom of God!

I used to think that the finest thing on earth was self-sacrifice. It was a great mistake. This picture of ‘The Pioneer’ reminds me that there is a form of sacrifice compared with which self-sacrifice is a very tame affair. I say that the picture reminds me; for it was the Bible that taught me of that sacrifice supreme. Take two classical stories from the Old Testament, both of which are recited in that glowing chapter that Dr. Jowett calls ‘the Westminster Abbey of the Bible’ — the eleventh chapter of the Epistle to the Hebrews. The stories are those of Abraham’s sacrifice of his son and Jephthah’s sacrifice of his daughter — only children, both of them. What a small thing, in comparison with either of these sacrifices, self-sacrifice would have been! Abraham would gladly have died a hundred deaths rather than have lifted the knife against’ his son, his only son Isaac.’ And how cheerfully Jephthah would have gone to the altar if by so doing he could have saved his daughter! There are few passages, even in the Bible, more charged with tender emotion than those two phrases, ‘Take now thy son, thine only son, Isaac, whom thou lovest,’ and ‘She was his only child: beside her he had neither son nor daughter.’

I know that there are those who, like Principal Douglas, think that Jephthah did not slay his daughter upon the altar, but resigned her to a kind of convent life. As to that, there are only two things to be said. First of all, I cannot imagine that any one who has read Dr. Marcus Dods’ monograph, or Dr. Alexander Whyte’s lecture, or Dean Stanley’s illuminating exposition, can hold that view. As Dean Stanley says, ‘A more careful study of the Bible has brought us back to the original sense. And with it returns the deep pathos of the original story, and the lesson which it reads of the heroism of the father and the daughter, to be admired and loved, in the midst of the fierce superstitions across which it plays like a sunbeam on a stormy sea.’ And the second thing is that, for my present purpose, it does not affect the argument. One of the most touching letters in our literature is the letter written by Lord Russell of Killowen, recently Lord Chief Justice of England, to his daughter May, on her resolving to enter a convent. ‘My darling child,’ Lord Russell says, ‘God’s will be done! It is a terrible blow to your mother and me! We hoped, selfishly no doubt, to have your sunshiny nature always with or near us in the world — a world in which we thought, and think, good bright souls have a great and useful work to do. Well, if it cannot be so, we bow our heads in resignation. We have no fear that you will forget us. After all, it is something for us, poor dusty creatures of the world, with our small, selfish concerns and little ambitions, to have a stout young heart steadily praying for us. I know we can depend on this. I know also that you will not forget your promise to me, should serious misgivings cross your mind before the last word is spoken. I rely on this. God keep and guard you, my darling child, is the prayer of your father.’ No-body who has read Lord Russell’s biography will ever be seriously affected by the alternative presented in the case of Jephthah’s daughter.

The point is that the sacrifice of one who is dearer than life itself is manifestly a greater sacrifice than self-sacrifice. It is such a sacrifice that Mr. McCubbin has painted. It is by such sacrifice that our Australian scrub has been sanctified. It is made as sacred as a shrine, and its sands more precious than gold. We take off the shoes from off our feet, for the place whereon we stand is holy ground. And it is such a sacrifice, under either interpretation, that Jephthah made. The Book of Maccabees celebrates the virtues of that noble Jewish mother who stood by whilst, one after another, her seven sons were cruelly tormented and slain. As first one and then another was tortured, she pleaded with each, as he loved her, to suffer and die rather than prove false to his father’s faith. And the story of her own martyrdom at the end of the chapter reads quite tamely after the thrilling pageant that has passed before. Her sacrifice of her seven sons, who were more to her than her own flesh and blood, was the sacrifice supreme. The sacrifice of herself seems small in comparison. That is the lesson that I learn as I gaze on Mr. McCubbin’s picture. If only the pioneer’s struggles had led to his own death! That would have been a very little price to pay. But that cross in the scrub! Oh, yes, the pioneer knew, and Abraham knew, and Jephthah knew, and that noble Jewish woman knew, and Lord Russell of Killowen knew, that there is a sacrifice infinitely greater than self-sacrifice.

There lies before me an old copy of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. How we underrate many of these stories, as though the lions, or the stake, or the rack, represented the real torture! That is merely self-sacrifice; but there is a greater wonder here for those who have eyes anointed to see it. Here, for example, is the story of Perpetua, ordered, for being a Christian, to be thrown to wild beasts at Carthage. Perpetua was a young widow, aged twenty-six, with an infant child at her breast. Her aged father visited her in prison, and implored her on his knees, for the sake of his grey hairs, to make some offering to the Roman gods. Indeed, so passionate did he become in his frantic anxiety to save his daughter that he tried to carry her off, and received a staggering blow from one of the prison officers. Perpetua said that she felt that blow on her old father’s head more than anything that she herself had suffered. Now, wherein lay the martyrdom of Perpetua? The pictures would have us believe that it consisted in being torn to pieces by wild beasts. I do not believe it. That is mere self-sacrifice. The sacrifice supreme was made when she kissed her baby for the last time, and threw her arms about the bowed and broken form of her father, whose old age she was leaving comfortless. It cost poor Perpetua little to sacrifice herself, but it broke her heart to sacrifice their happiness and welfare.

Now these two— Perpetua’s aged father and Perpetua’s little babe — are representative characters. They are like symbols, emblems, types. They stand for a great deal. I have seen a young missionary’s face blanch as he looked towards a horrid climate steaming with fever and malaria. But the agony was not for himself. It was as easy to die among those pestilential bogs and swamps as anywhere else. But what of the old folks at home? Here is Perpetua’s father over again! We remember how, when W. C. Burns set out for China in 1846, his mother found it so hard to part with him, that, after walking some distance with him from the old homestead, she seemed unable to endure any longer the intensity of her emotion, and giving him a vigorous push, said: ‘There, noo, I’ve gi’en thee to the Lord! Go!’ It is that kind of thing that makes the departure so hard. It is the problem of Perpetua’s father.

Perpetua’s child, too; I think I have seen its counterpart What of Livingstone and his familv in the desert? He saw his children dying of fearful thirst under his very eyes. ‘The agony of it,’ Mr. Silvester Home says, ‘must have nearly killed him.’ ‘The less there was of water, the more thirsty,’ Livingstone says, ‘the little rogues became. The idea of their perishing was terrible!’ Here is the anguish of the pioneer! What is self-sacrifice compared with this? And that little grave in the desert where they buried the baby! ‘Hers,’ says the father, ‘was the first grave in all that country marked as the resting-place of one of whom it is believed and confessed that she shall live again!’ As I stand beside this little tomb in Central Africa, I am back once more with Perpetua saying good-bye to the child of her bosom. This, surely, is the sacrifice supreme. And then I see Livingstone digging with his own hands that other grave under the great baobab-tree at Shupanga, and moaning, ‘Oh, Mary, Mary, my Mary! I loved you when I married you, and the longer I lived with you the more I loved you!’ And when I reverently gaze upon this, I look again at Mr. McCubbin’s third picture — the pioneer kneeling by the lonely cross — and I fancy that I am not far from the very heart of things.

History and experience abound with instances of this sacrifice that is greater than self-sacrifice. In his autobiography Dr. Thomas Guthrie tells of a visit paid him by the great Dr. McCrie, the historian of John Knox. ‘My second son, James,’ says Dr. Guthrie, ‘was then an infant in the nurse’s arms, and I distinctly remember the great and good man taking him in his arms, and saying, as he held out the child to me, and in allusion to the martyrdom of that other James Guthrie, the Covenanter, “Would you be willing that this James Guthrie should suffer, as the other did, for the Church of Christ?” ‘And later on, in the great Disruption days, the scene came back with poignant force to the memory of Dr. Guthrie. For when the ministers left their kirks and manses for conscience’ sake, it was the wives and children that suffered most. In one home — a home that had known many cradles and many coffins, and in which every flower and shrub and tree was dear to them’ — Guthrie heard, through the partition, the moaning of the minister’s wife. ‘That woman’s heart was like to break!’ ‘In another locality,’ he says, ‘there was a venerable mother who had gone to the place when it was a wilderness, but who, with her husband, had turned it into an Eden. Her husband had died there. Her son was now the minister. She herself was eighty years of age. When I looked upon her aged head, white with many snows and sorrows, I felt that it was a cruel thing to tear her from the house that was dearest to her on earth.’ Yes; the sacrifice of the Disruption ministers was far more than self-sacrifice. It was the sacrifice of children and wives and mothers like these. They went out to starve on the moors and hillsides of Scotland with such heartrending cries in their ears. That was the sacrifice supreme.

And so, as I turn again to Mr. McCubbin’s painting, I seem to be looking, not at a picture, not at three pictures, but at a gallery. For there are others, companion pictures, ranging themselves about it. A picture of Abraham standing beside the prostrate form of ‘his son, his only son, Isaac.’ A picture of Jephthah offering his daughter on the altar in the valley. A picture of the noble Jewish matron and her seven heroic sons. A picture of Perpetua and her tearful farewell to her infirm father and her clinging babe. A picture of Livingstone in his anguish beneath the great baobab-tree. A picture of the Disruption ministers going out into the unknown accompanied by weeping women and hungry children. A picture of John Bunyan, too, kissing, before going to Bedford Jail, the upturned face of his sightless girl. ‘Poor child! how hard it is like to go with thee in this world! Thou must be beaten; must suffer hunger, cold, and nakedness; and yet I cannot endure that even the wind should blow upon thee!’ Here is a stately gallery! A glorious company this, a goodly fellowship, a noble army of testifiers!

And as I still gaze at this great gallery, all the pictures, including Mr. McCubbin’s picture, seem to range themselves around one great central canvas. I said just now that, as I turned from the scene beside Mary Livingstone’s grave, and from the picture of the pioneer beside the lonely cross, I felt that I was not far from the heart of things. For surely these sacrifices — each of them infinitely greater than self-sacrifice — are but faint radiations and dim reflections of the love that is everlasting, the Sacrifice Supreme! God so loved the world that He gave His only-begotten Son! Gave His Only Son! God Gave His Son! All these sacrifices that are greater than self-sacrifice point steadily up to that! We may leave the gallery now, and we shall leave it with bowed heads!

F.W. Boreham

0 Comments