IX

THE EXHILARATIONS OF LIFE

Life breaks down first of all on the side of its exhilarations. ‘They have no wine!’ said Mary at the feast in Cana of Galilee. And she might say it still. It is life’s first point of collapse. Health holds out. Money increases. Friends multiply. We have abundance to eat, plenty to drink, and warm beds to sleep in. But the wine fails. Life somehow loses its sparkle and its sprightliness. The gaiety and the elasticity depart. An eminent art critic stood before a picture. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘it is very good; but it lacks that’ — expressively snapping his fingers. Every man discovers sooner or later that he lacks ‘that.’

Here are a pair of illustrations picked at random. The first is from Mrs. Barclay’s Mistress of Shenstone. ‘Yes,’ replied Jim Airth, ‘seven o’clock on the first of June I stood at the smoking-room window, at a loose end of all things; sick of myself, dissatisfied with my work, tired of everything,’ The second is from one of Madeline Cope’s beautiful letters in M. E. Waller’s Woodcarver of ’Lympus. ‘Before I knew it, Hugh,’ she says, ‘I was dragging anchor, losing the dear, sweet, childlike faith I had kept as my best heritage from my father and mother, and, with it, losing much of the spontaneous joy of life.’ That is it exactly. ‘Dragging anchor,’ ‘Losing the spontaneous joy of life,’ ‘They have no wine!’ The vim and the vivacity have vanished. Not that we become positively miserable. No. There are no tears. It does not rain. The sun merely hides itself behind dense clouds. The birds hush themselves into sullen silence. The song dies from the lips. Life becomes sombre and grey. That loss of sunshine is, I repeat, the first breakdown that most lives know. They do not become morbid or melancholy. They simply lose the exquisite exhilaration of life. Laughter, which used to burst out like a sparkling spring on a grassy hillside, has now to be forced, like the tainted dribble of a rusty pump. It is no longer a luxury to be alive. ‘They have no wine!’ That is all. And it is quite enough.

For it is not too much to say that the whole of a man’s life takes its tone and colour from his behaviour at this crisis. ‘Before you have finished,’ said Myrtle Reed’s old violin-master to his young pupil, ‘before you have finished, the world will do one of three things with you. It will make your heart very hard, it will make it very soft, or else it will break it. No one escapes!’ Precisely! That is literally so. No one escapes. And the world usually makes up its mind as to which of these three things it will do with a man when it sees what course he himself pursues when exhilarations fail — when the wine runs out. For at that critical juncture three roads meet. Exhilarations fail; and a man makes up his mind to do without. That is the first possibility. He simply reconciles himself to grey days. He defiantly sets his teeth, and clenches his fist, and vows that he will see the horrid thing through. He becomes cynical, taciturn, sour. That is what the old violin-master meant when he said that the world may make your heart very hard. Or, at the other extreme, there is a second alternative. A man may do as Mary did. ‘When they lacked wine, she said unto Him, They have no wine!’ There is no wisdom in the heavens above nor on the earth beneath that can compare with that. Surely that was what the old music-master meant when he said, ‘or it will make your heart very soft!’ But there is the third course. A man may seek compensations. True, he feels that he has lost the sunshine. But what of that? Are there no other lights ? True, the birds no longer sing. But what then? Is there no other music? He seeks in ribald revelry to forget the finer flavour of that wine that he may drink no more. Along that road he finds disappointment, disillusionment, and heartbreak at the last. Yes; the violin-master was quite right. ‘Before you have finished, the world will do one of three things with you. It will make your heart very hard, very soft, or else break it. No one escapes!’

We come to places at which the world treats us as it treated Livingstone’s native comrades. We all remember their sensation when, at Loanda, those Central Africans saw the sea for the first time. ‘We marched along with our father (Livingstone),’ they tell us, ‘believing that what the Ancients had always told us was true, that the world had no end. But all at once the world said to us, “I am finished, there is no more of me.”’ Here is the point of exhaustion; and it is around that very experience, in another realm, that some of the most affecting passages in our literature gather. The world has come to an end. The wine has failed; and the heart has sought desperately, and in vain, for its lost exhilaration.

I cite two witnesses — George Fox, the founder of the Quakers, and Cardinal Newman. In most respects the two men stand in striking and dramatic contrast. History can scarcely present two more clear-cut variations. But, just on that account, their evidence is the more valuable to us as we watch their divergent experiences converge upon this crucial point. Everybody who has read Mr. A. C. Bickley’s great biography of Fox will recall the passages that describe, in effect, the failure of the wine. It happened when he was at the age of twenty; and his experience was so pathetic and so bitter as to move the compassion of both Macaulay and Carlyle. ‘Wherever he went,’ Mr. Bickley tells us, ‘people pitied the gentle melancholy youth, and many were anxious to befriend him. While at Barnet, he was almost in despair, and he spent many hours walking up and down in the Chace, solitary and sad, trying to find some relief.’ Here he is, then; this youth of twenty, who feels that the wine has failed, and that life is left to him without gaiety. He is ‘trying to find some relief.’ Let us follow him in his search. ‘One jolly old clergyman,’ says Macaulay, ‘told him to smoke tobacco and sing psalms; another counselled him to go and lose some blood. From these advisers the young inquirer turned in disgust to the dissenters, and found them also blind guides.’ ‘The clergy of the neighbourhood,’ says Carlyle in Sartor Resartus, ‘listened with unaffected tedium to his consultations, and advised him, as the solution of such doubts, to drink beer and dance with the girls!’

In the story of the Cardinal there is a pitiful piece of correspondence between Newman and his mother. The earnest young student writes to his parents, telling of his doubts and fears and spiritual struggles. It is clear that the wine has failed. But the tragedy occurs, not in Newman’s plaintive letters to his mother, but in her reply to him. ‘Your father and I fear very much from the tone of your letters that you are depressed. We fear you debar yourself a proper quantity of wine.’

Now, here are two young men — historic figures both of them. Both have felt life’s first collapse, the failure of the wine. Both have reached, in consequence, the crisis from which all subsequent experience takes its colour. And both are pointed down the wrong road by those to whom they are entitled to look for guidance. It would be easy to devote my remaining space to an impressive application of a very obvious moral to all parents and pastors. But that would be beside my present mark.

‘Drink beer!’ said the old clergyman to young George Fox. ‘Take wine!’ said Mrs. Newman to her brilliant son. These are the pitiful expedients that blind guides prescribe for aching hearts! Beer and wine ! Beer for Fox and wine for Newman! Think of it! What a lurid light is thrown by these incidents upon our colossal national drink bill! I cannot now contemplate these hundreds of thousands of pounds being spent throughout the Empire every year on beer and wine without conjuring up before my fancy millions of spiritual tragedies. Here are mystics of the measure of Fox, and thinkers of the type of Newman, painfully conscious that life’s innermost exhilarations have failed them, seeking frantically to assuage their soul’s intense desire by drinking beer and wine! It is a spectacle for men and angels! There are some aspects of the temperance question that provoke the passion of an orator; this aspect appeals to emotions that do lie too deep for tears. It is the old, sad blunder. ‘Soul, thou hast much goods laid up!’ As though a man could feed his soul on corn! As though the soul of Fox could be brightened by beer! As though the soul of Newman could be exhilarated by any earthly vintage!

No, no, no! It will not do! There is a more excellent way. And Mary knew it. ‘She saith unto Him, They have no wine.’ Even Nature gives mysterious and subtle hints of perennial exhilarations rushing out of apparent exhaustions. Here is an illustration offhand. I have beside me two lectures. One is by Sir William Ramsay, K.C.B., of London, on the ‘British Coal Supply.’ The other is by Professor Soddy, of Glasgow, on ‘The Interpretation of Radium.’ Sir W. Ramsay’s lecture is really on ‘Exhaustion,’ Professor Soddy’s is really on ‘Exhilaration.’ Sir W. Ramsay says that coal is the one source of energy to the British people. It is by means of coal, he argues, that all our manifold activities are sustained. But the coal-fields of the United Kingdom, he tells us, will only last for 175 years. That is decidedly depressing. But listen to Professor Soddy. ‘The revelations of radium,’ he says, ‘have shown that the world is not, as had been supposed, slowly dying from exhaustion, but bears within itself its own means of regeneration, so that it may continue to exist in much the same physical condition as at present for thousands of millions of years.’

It is a parable. God has set His wonderful exhilarations over against our pitiful exhaustions. Every student of history knows that Jesus came into an exhausted world. Its ancient civilizations were all played out. Like a clock, the whole thing was in danger of running down. As Matthew Arnold says, in ‘Obermann,’

On that hard pagan world disgust

And secret loathing fell;

Deep weariness and sated lust

Made human life a hell.

Then Jesus came, and changed the face of everything. And in Him the nations found a fresh exhilaration. Here, surely, is a gospel worthy of our most persuasive powers! What an invigorating and exhilarating thing a conversion really is! I have just read Mr. Edward Smith’s Mending Men. Here are men of wasted lives, jaded powers, flagging forces, dissipated energies, and depleted moral resources. Life was exhausted at every point. ‘They had no wine.’ Then into those beggared and bankrupt lives Jesus came. They were converted. And exhilarated! Like the prodigal, they began to be merry. That is always the way. Dr. Campbell Morgan provoked a smile the other day by rendering the classic phrase of Habakkuk in this way: ‘I will jump for joy in the Lord; I will spin round with delight in the God of my salvation.’ I have no doubt that the Principal of Cheshunt’s translation is sound. I am quite sure that it is true to the facts of spiritual experience. Religion is a revelry.

Heaven above is softer blue,

Earth around is sweeter green,

Something lives in every hue

Christless eyes have never seen.

Birds with gladder songs overflow,

Flowers with richer beauties shine,

While I know, as now I know,

I am His, and He is mine.

Any man who has once discovered what a brave and bracing thing a conversion really is will be hungry to witness another. The beautiful phenomenon will fascinate him, and, like Mary, he will sadly look on an exhausted humanity, and say to his Lord, ‘They have no wine!’ And he will be restless and ill at ease until the vessels are filled to the brim.

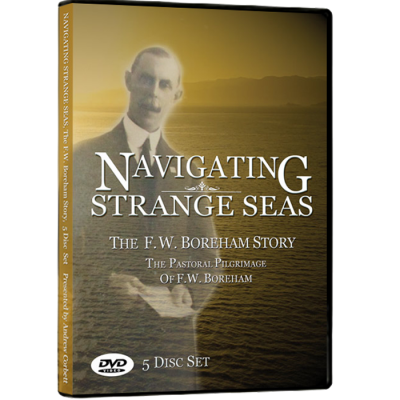

F.W. Boreham

0 Comments